Weavers Think About Weaving

Write metaphors with world-building in mind.

by Jack Windeyer

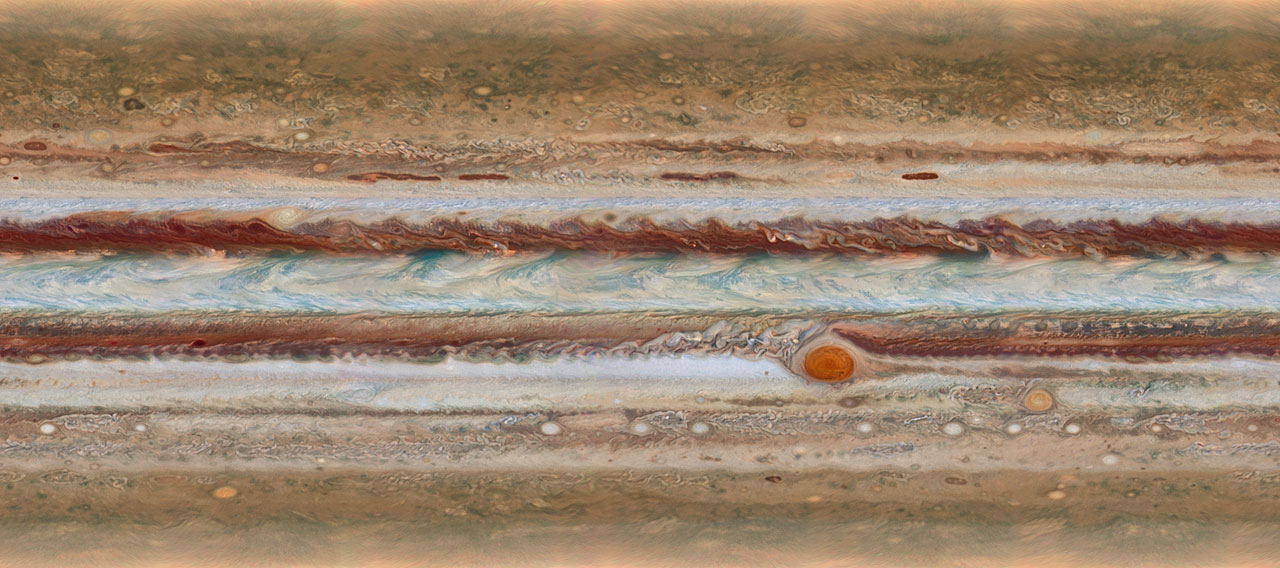

Jupiter At A Glance- NASA, ESA, A. Simon (GSFC), M. Wong (UC Berkeley), and G. Orton (JPL-Caltech)

Metaphors and similes must be consistent, and I don’t only mean internal consistency. Yes, you should avoid writing mixed metaphors. But there is an external, story-wide type of consistency that you should also consider.

Here’s what I mean: if you’re writing a story in third person limited and your viewpoint character is a mechanic from Wells, Nevada who’s just seen a flying saucer, she’s not going to describe it in the same way that a physicist would (unless you’ve already established that she’s a beleaguered PhD candidate running away from her problems by working in her father’s shop). She’s more likely to say the UFO looked like a flying hubcap.

This is true for all fiction, but it is especially true for speculative fiction. You’re building a world unlike our own in possibly profound ways and only by keeping it consistent can you keep the reader’s trust.

Carrie Vaughn wrote an incredible novelette called Astrophilia that Gardner Dozois picked out for one of his Year’s Best collections. It’s a story about Andi who is a weaver living in a post-apocalyptic world that has reverted to simpler times.

When Vaughn employs a simile to describe Andi and her roommate’s opposite schedules, you can bet that it won’t concern ships passing in the night. That’s because weavers think about weaving:

Andi had spent the day at the wash tubs outside, cleaning a batch of wool, preparing it to card and spin in the next week or so. She’d still been asleep when Stella got up that morning, but must have woken up soon after. They still hadn’t talked. Not even hello. They kept missing each other, being in different places. Continually out of rhythm, like a pattern that wove crooked because you hadn’t counted the threads right.

If Vaughn had instead used a metaphor unrelated to the plot it might jar the reader’s experience of the story. By contrast, the externally consistent metaphor aids the reader by maintaining the world that the author is so carefully building.